Posted on 18 March 2024

Seafood Magazine: Hot and cloudy waters ahead: forecasting the value of the pāua fishery

- 6 Minutes to read

Shared with permission from Seafood New Zealand Magazine - March 2024

Flourishing fisheries rely on understanding environmental risks, uncertainties, and opportunities in a changing climate.

The pāua fishery is an ideal test subject for understanding the impact of climate change — hotter seas and more sediment affect the size and health of pāua, and the value of the fishery. Finding ways to adapt, limit stressors, and invest in restoration rests on being able to forecast scenarios in a changing environment. A better understanding of the risks can inform response strategies and investments in fisheries.

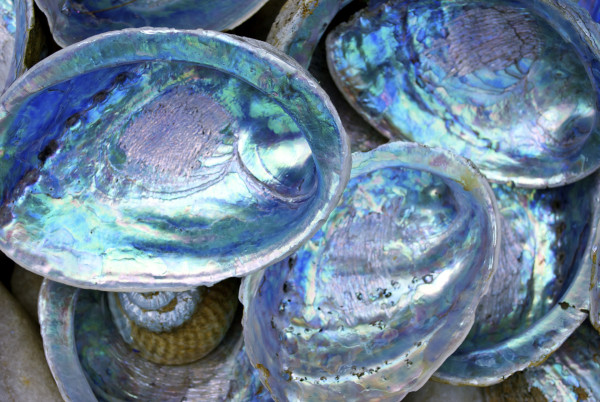

Image: Terra Moana

New research from the Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge has tapped into expertise from biology, business, and banking and explored a way to embed the impact of climate change into decision-making.

Researchers have released a new bio-economic risk model for the PAU2 fishery, which means fishers, iwi, and investors can test different scenarios on the potential value of the fishery. These scenarios could help drive strategic, organisational and management change, and adaptive business strategies.

Co-researcher, Katherine Short says the research project benefited from bringing together biology and economics.

“The holy grail is bringing natural systems knowledge together with economic and financial knowledge. If you can get those things to work and talk to one another, your recommendations are so much stronger.”

Tony Craig, co-researcher, says, the model can explore the ‘what if’s’ and what that might mean for different fisheries.

“At the industry, fishery level, collective action is needed to enable responsible quota owners to progress fishery management improvements.”

An easy-to-use bio-economic model

The Pāua Quota Valuation Bio-Economic Model is a simple, easy-to-use model with standard spreadsheet software (Excel). The model has forty worksheets — two of which take information from users. The model performs calculations, aggregates and graphs results, and gives financial value information.

Users can choose from up to 31 different PAU2 fishery sub-zones. Each sub-zone has its own sheet that calculates annual recruitment success, growth, distribution by length buckets, weight, recreational, customary, and illegal catch by numbers and tonnage, commercial catch by numbers and tonnage, instantaneous mortality, and opening and closing balance numbers of pāua each year under the chosen scenario.

Users choose the percentage of the population in each sub-zone and create their own scenarios related to recruitment success, instantaneous mortality, growth transition, fishing mortality, and valuation factors over time.

Katherine says the scenarios are proxies for types of environmental change. The aim of the model is to help avoid situations where people say,

“If I had known what the lost quota value would be, what could I have spent on investing in improvement, minimising sediment, and in remediation?”

Using the scenarios, the model produces four types of graph.

- A comparison of the total allowable commercial catch (TACC) with the estimated commercial catch

- The capitalised value and the estimated commercial catch each year in kilograms

- The aggregate closing population of pāua, with the number of pāua available for fishing each year, and the weighted average length of all pāua

- The weight of pāua available for fishing that remains after assumed customary, recreation, and illegal catch (CRIF), the estimated commercial catch, and the estimated percentage of aggregate pāua that have reached the minimum legal size for fishing each year.

The model was developed in four stages

Researchers developed the model in stages.

- Establish a baseline.

- Model the biomass.

- Calculate the value of quota.

- Build and present the model.

Storm Stanley, chair of the Pāua Industry Council says confidence drives the value of pāua.

“Modelling can help tell what’s coming and what can we do about it. The threats are real — more marine heatwaves, acidity, storms, flooding, and sediment.”

Tony says climate risk modelling is new, complex, and challenging. The model isn’t predictive, but a starting point that can be adapted and used more widely in future.

“Users can choose their own assumptions and plug and play. Pāua are the canary in the coalmine. See what happens to the value of the catch in the different scenarios? Have a play.”

He says the model is a structurally sound financial model that can be adapted with future data. More information is still needed, for example better knowledge of interrelated stressors. Better information can come from working together.

Financing a blue economy — collaboration is key

In a changing climate, finance is an important piece of the puzzle in upholding the value of the pāua fishery.

As one of New Zealand’s largest lenders to the seafood sector, ANZ was part of the research team.

“We can see that to adequately understand the risks and ensure the sustainability and resilience of the pāua industry, it’s vital that the industry collects and shares data on these environmental changes,” says Dean Spicer, ANZ’s Head of Sustainable Finance.

“This data can help inform better decision making and give us the opportunity to consider how we can mitigate those risks.”

He says rising stakeholder expectations about sustainability and new regulations that require New Zealand’s largest financial institutions to report on their climate-related risks and opportunities are also driving change.

“To attract investment, businesses need to be able to understand climate risks and explain how risks are incorporated into their strategy,” says Dean.

Katherine says that collaborating on data collection is important for the sector.

“You don't want a dozen buoys run and operated by a dozen groups, all paying for and collecting their data separately. You want two or three buoys in the right places, all paid for by the dozen groups that care and then slicing and dicing the data.”

It’s about a coordinated effort that will reduce costs and provide data for all parties.

Working together across disciplines is key to this type of modelling being used more widely and making a difference in sustainable blue economy businesses responding to climate change, says Katherine.

“Everybody along that supply chain from diver to processor, Moana New Zealand to quota owners, the iwi that own Moana New Zealand — everyone could share in the cost of environmental monitoring and the environmental response.”

“When we prioritise the health of the pāua fishery as an indicator of success, we can have a completely different mountains-to-sea approach”, says Katherine. “When different perspectives are brought together — like modelling, industry, business perspectives, and valuation — the opportunities are enormous.”

“The small things you could actually do matter. The success of the new model is thrilling.”