Why do we need EBM?

Aotearoa New Zealand has a vast marine estate that is increasingly under pressure, and the current legal framework for marine management is complex and fragmented.

Aotearoa New Zealand has a vast marine estate that is increasingly under pressure, and the current legal framework for marine management is complex and fragmented.

There is a growing conflict between Aotearoa New Zealand’s many uses of the marine environment, including its important marine economy and protection of the marine environment.

Ecosystem-based management (EBM) involves managing the marine environment in a holistic and inclusive way. This means that competing uses are managed in a way that does not degrade the marine environment.

Governance structures that provide for Treaty of Waitangi partnership, tikanga and mātauranga Māori.

Humans, along with their multiple uses and values for the marine environment, are part of the ecosystem.

Collaborative, co-designed and participatory decision making processes involving all interested parties

Based on science and mātauranga Māori, and informed by community values and priorities.

Marine environments, and their values and uses, are safeguarded for future generations.

Flexible, adaptive management, promoting appropriate monitoring, and acknowledging uncertainty.

Place and time specific, recognising all ecological complexities and connectedness, and addressing cumulative and multiple stressors.

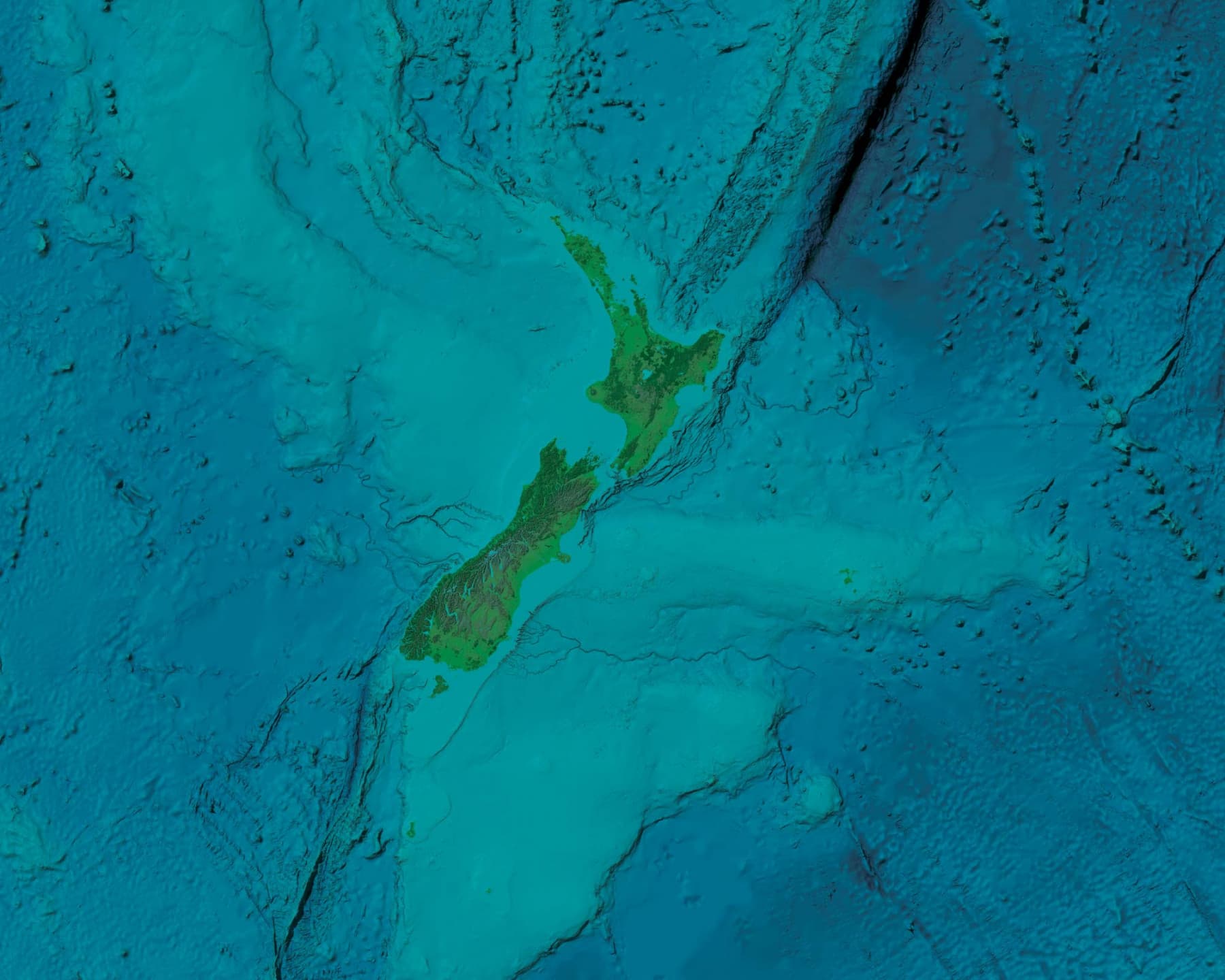

New Zealand’s marine estate is 20 times larger than our land mass, and we have the 4th largest Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the world. New Zealand’s marine resources include fisheries, aquaculture, tourism, oil and gas, minerals, renewable energy, shipping and more.

The sea is also an important part of the New Zealand lifestyle and culture – for food, recreation and spiritual well-being. 75% of New Zealanders live within 10 km of the coast, and Māori connections with the sea are particularly strong.

New Zealand’s marine estate, our Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), is 20 times larger than our land mass and the 4th largest in the world.

New Zealand’s marine economy includes fisheries, aquaculture, tourism, oil and gas, minerals, renewable energy, shipping, social enterprise and more.

The sea is an important part of our lifestyle and culture – for identity, food, recreation and spiritual wellbeing. 75% of New Zealanders live within 10 km of the coast, and Māori have long standing ancestral and other connections with the sea.

The legal framework applying to the management of Aotearoa New Zealand’s marine area is complex and fragmented.

At least 20 pieces of legislation apply to the marine environment and many different central and regional government agencies are responsible for administering the law and managing the marine environment.

New Zealand’s legislation was developed for a range of different purposes (eg marine mammal protection, conservation, regulation of fisheries) and there is no consistent management approach across all the different types of legislation. Some legislation was first passed more than 50 years ago.

There are also some Acts that only apply to a particular area of New Zealand, such as the Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Management Act 2005 which applies only in Fiordland. Some provision has been made for Māori customary rights and those under Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi in the marine area but these have yet to be fully resolved, and may result in additional place-specific management arrangements.

Together, this means that New Zealand’s marine environment is not managed holistically. At the same time, there are increasing pressures on our coasts, oceans and marine resources.

The Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) provides for some partnerships with Māori. It recognises connectedness, cumulative effects and a wide range of human values. It provides for the establishment of environmental bottom lines and decision-makers can draw on a wide range of knowledge.

It also places positive obligations on agencies to monitor the state of the environment. The New Zealand Coastal Policy Statement 2010 provides more specific direction on how the RMA is to be applied to the marine environment. Credit: Dave Allen NIWA

The Fisheries Act 1996 provides several valuable customary management tools to enable, to some extent, the application of tikanga and mātauranga Māori in defined marine areas.

For example, it provides for mātaitai reserves which are managed by a kaitiaki/tiaki through making bylaws to manage fishing activity. Mātaitai are normally closed to commercial fishing. For more information see: Sustainable Seas discussion paper on customary management and ecosystem-based management Overview of fisheries legislative framework on the Ministry for Primary Industries website

For example, although the Fisheries Act references broader marine environmental considerations, management largely focuses on implementing a single ‘stock’ management framework based on the concept of maximum sustainable yield. This approach does not recognise ecological complexity, ecosystem connectedness or the impact of cumulative stressors.

The Fisheries Act also does not include statutory public participation processes which means it is out of step with other environmental legislation in New Zealand. The EEZ and Continental Shelf (Environmental Effects) Act 2012 is weak on ensuring a healthy environment, with the legislation giving environmental matters no particular priority over economic benefits.